-Siddartha Mainali, Rachana Upadhyaya, Ichchhuk Poudyal

Photo (above): A woman learning to use the application developed for the cooperative.

In February, in a remote village of Nepal, men and women from a local cooperative gathered to learn about a digital app designed to enhance farming and agricultural activities. The audience represented a snapshot of the rural community, including farmers, politicians, and young people.

They had gathered at the invitation of GLOW’s Participatory action research project, Co-producing a shock-resilient business ecosystem for women-led enterprises in Nepal (CREW), to shed light on how communities, policymakers and digital innovators can best use digi-tech to enhance agriculture.

What stood out most in this scene was the workshop trainer, Sunita.

Sunita’s position signals a shifting gender dynamic in rural communities where women are joining men as early adopters of digital technologies. It is a positive trend, which can help transform rural livelihoods, but more can be done to overcome the constraints facing women in utilising these tools.

App adoption among women farmers

The CREW project, led by the Southasia Institute for Advanced Studies (SIAS), seeks to identify what makes women farmers adopt mobile apps for use in agriculture, in Nepal. It initiated the technology training programme that Sunita led, with the aim of educating communities, especially women, on the use of mobile apps for farming.

In addition to the training, a quantitative survey of more than 350 women was also conducted, with data supplemented by a series of focus groups discussions, key informant interviews, and reflections from participatory action research.

Collectively, the results revealed the potential of digital technology to enhance agricultural practices in rural communities. However, several constraints hinger widespread uptake, including: structural barriers, gender-related stereotypes, (il)literacy, and apps which do not fit local contexts.

Digital infrastructure constraints

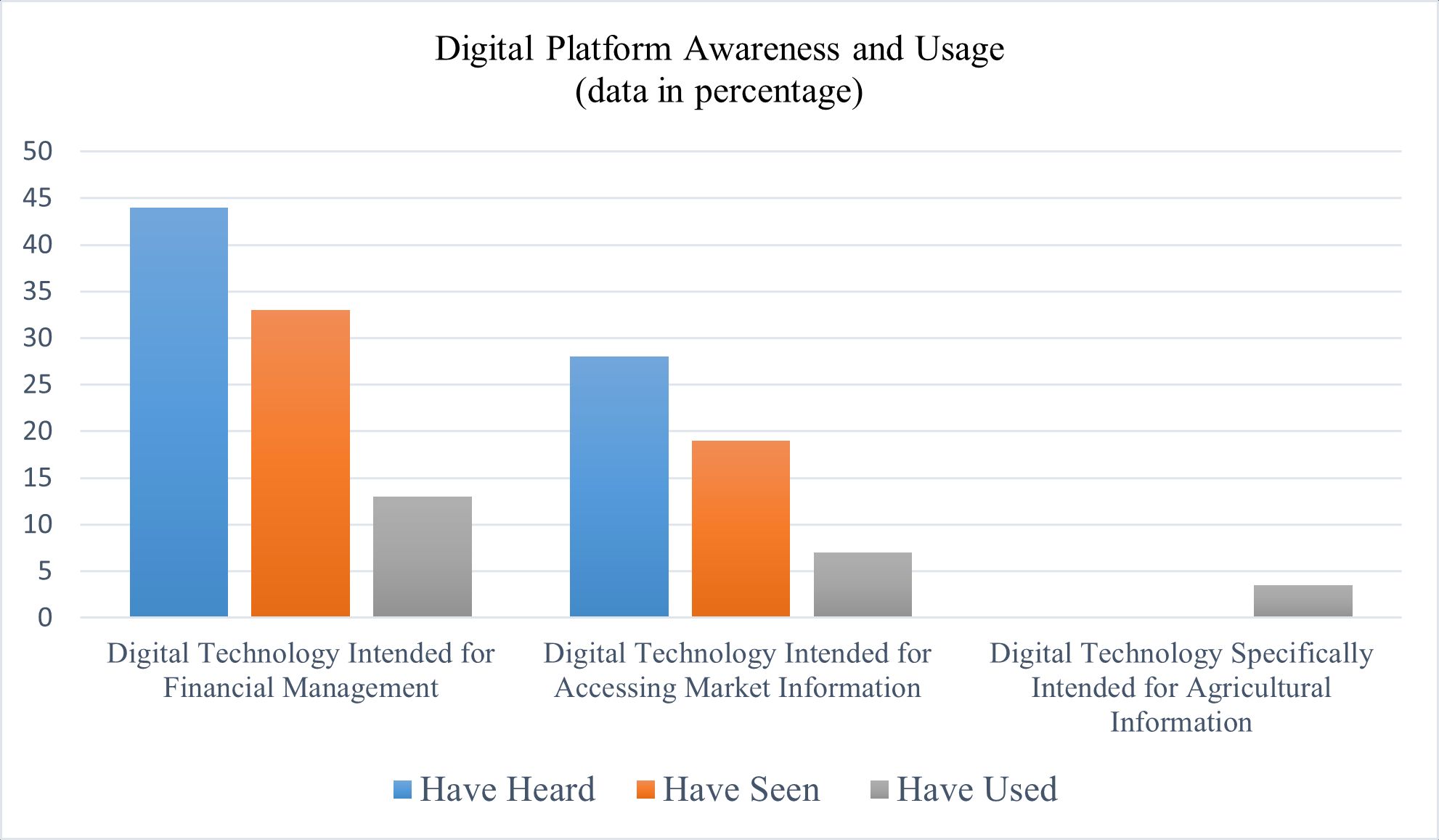

Digital tools and mobile apps for agriculture, such as Smart Krishi and Farm2Fork, are gaining in usage, according to CREW field observations. However, their adoption rate is sporadic in rural areas, and they rank second to more traditional methods. This could be explained by structural barriers such as inadequate digital infrastructure.

Indeed, responses from communities participating in the CREW study report rely primarily on word-of-mouth communication for agricultural market information. That means getting insights on prices and demand, quality of inputs, agricultural methods, and weather information from sources such as inter-generational transfers of knowledge or conversations at local community agriculture markets.

That’s not to say mobile apps aren’t being used. Banking apps, for example, are popular with women in the study regions who receive remittances and who use the apps for paying bills. This uptake shows potential for progress with digi-tech for agriculture and highlights the need for more robust infrastructure to encourage wider adoption.

Figure 1: Exposure and Adoption of Digital Platforms for Agriculture, Markets, and Financial Management

Image

Financial autonomy and societal norms

Notably, 21% of the women in the CREW survey reported having more land titles than their male counterparts.

Additionally, over 30% of the women survey respondents described themselves as the head of their household. They also indicated a link between their status within the household and autonomy over financial and expenditure decisions, which included the decision to use digital technology.

According to the CREW survey, average annual mobile data expenses total NPR 2,716 (USD 20.58), which is by no means a small investment for those in rural communities. However, the CREW survey revealed that most of this expense is used on social media platforms like Facebook Messenger and Viber, and not on mobile apps supplying agriculture market information.

In fact, the survey revealed that purchasing mobile data to use social media is common among women and carries important implications for social dynamics. According to one focus group respondent, showing her mother-in-law YouTube videos has painted her as adept at using technology and increased her social capital within the family.

With the frequent absence of male family members due to migration for employment, rural women like her, especially of younger generations, are breaking gender stereotypes around their ability to use digital technologies.

Despite these positive gains, however, women remain a minority when it comes to financial decision-making, having a discernible impact on adoption of mobile apps of any type. As another respondent described it: “My husband sends remittance money to my father-in-law who then spends it at his will. I am scared to ask for money to purchase a suitable phone”.

Design of digi-tech for farming

Illiteracy and mobile ownership further constrain adoption of digi-tech solutions in rural Nepal. Over 45% of respondents could not read or write, and only 48% of respondents owned a smart phone at the time of the survey. Similarly, only 39% of women had access to the internet.

This raises questions about the design of available mobile apps developed for farming purposes. These tools, although useful, are generally not suitable for those in rural settings as they are designed with complicated touch interfaces, lack voice commands, and don’t display farming information in video format. The apps were also significantly constrained in offline mode, a feature which allows an app to be used without internet connection.

A lack of features like this may explain why only 3.5% of survey respondents reported actively using these apps. Low digital literacy may also contribute to this, with 35% of respondents saying they were unaware of the tools at all.

Recognising the potential

Despite constraints, survey respondents agree on the indispensability of digital technology. Indeed, 75% of respondents said they perceive mobile phones as useful tools in obtaining information for agriculture.

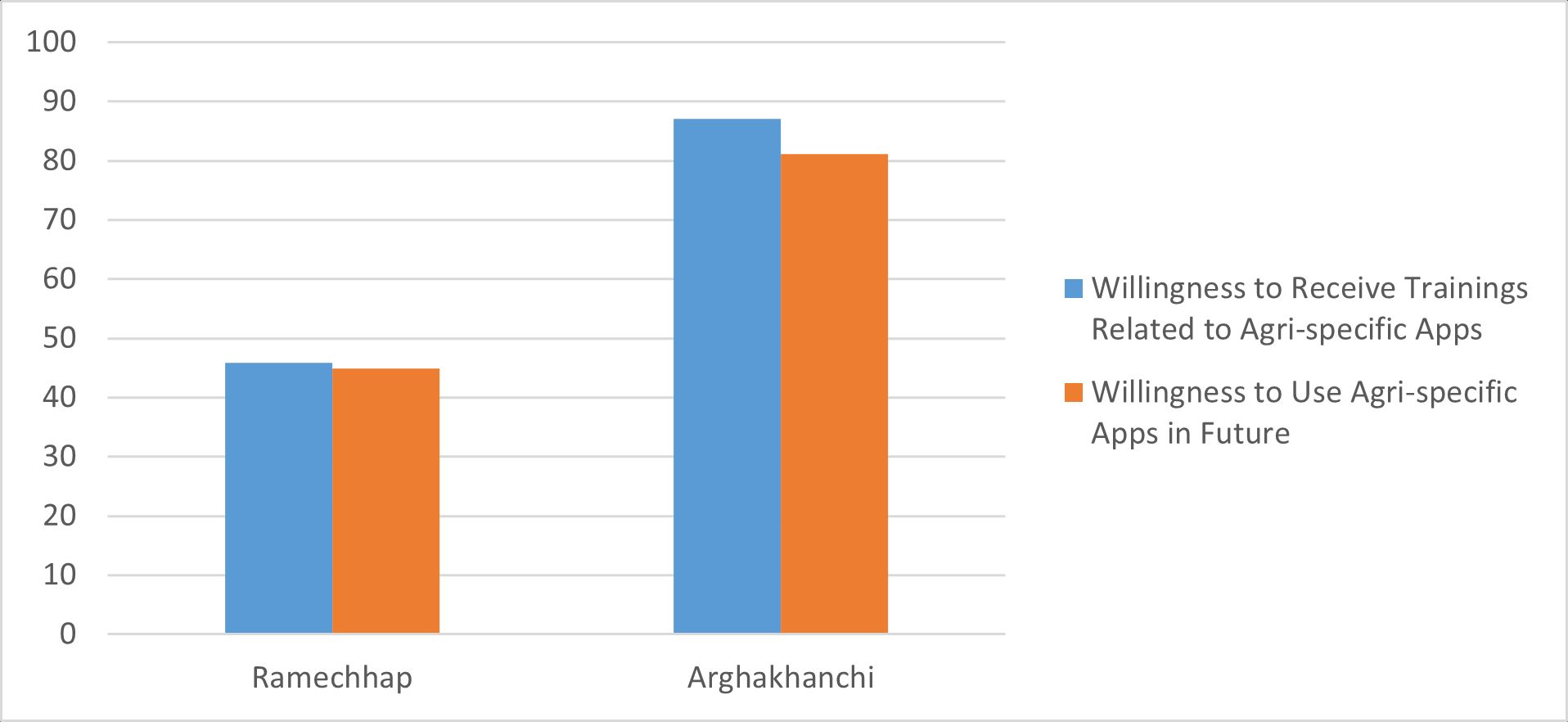

Over 95% said they had not received any training related to apps designed for agriculture at the start of the intervention, but 67% of respondents showed clear intentions to participate in app training.

Respondents also recognised the potential of mobile apps for improving rural agricultural practices and services, in particular for addressing present gaps in services such as limited access to the market and market information, agriculture extension services, and information on weather forecasts.

A significant 63% majority reported they could maximise agricultural output by adopting digi-tech in the future.

Figure 2: Interest in Training and Future Use of Agri-specific Apps (data in percentage)

Image

Co-producing agriculture apps

CREW findings indicate that technology uptake requires integration of context-dependent local knowledge along with user-friendly and intuitive interfaces. Co-producing app technology with users can ensure effective knowledge integration and adequate addressing of local needs.

Co-produced design could also circumvent barriers that are intrinsic to the community, yet ‘unseen’ or overlooked by technology developers. These factors include language proficiency of users, technological capacity to engage with complicated interfaces, and challenges from multiple log-in requirements.

The research also underscores the usefulness of information presented in video format and the integration of voice command features.

Future of digital access

Closing the gap in digi-tech adoption among rural women farmers in Nepal requires a multi-pronged approach inclusive of awareness campaigns, trainings, and building trust and confidence in technology. Infrastructure also needs to be in place, including affordable internet services and access to smartphones.

Internet availability is a significant constraint to rural uptake of digi-tech, but there is evidence this is slowly shifting. A locally-elected representative of one survey location reported having installed routers in public spaces of his ward. Building on this, local and national governments can think along the lines of affordable community-based internet hubs, and broadband expansion more generally.

It is important for interventions to address gender disparities as well, such as affordability, ease of use, and multi-functionality. While our respondents show positive trends in gender related stereotypes and disparities, the differences between rural and urban, and men and women, persist.

Digital literacy programmes and training targeted at women are also required. So is technology designed with consideration of the diversity of contexts and users. These enhancements would allow communities to benefit from improved communication, access to information, and new economic opportunities.

By ensuring technology fits its users, and that users are able to access its benefits, it is possible to create a level playing field where farmers, regardless of gender, will have opportunities to thrive in the digital age.

This blog article was first published at Gender Equality in a Low Carbon World June 14, 2024.

“Views expressed here are personal and not associated with any affiliated organisations”