–Daniela Soberon Garreta, University of Edinburgh

Environment & Development (E&D) fieldwork is complex, as it merges two intertwined but sometimes conflicting worlds in setting priorities. During the study trip, I experienced this tension firsthand. Alongside my MSc Environment & Development cohort from the University of Edinburgh (UoE), the UoE team, and under the guidance of the Southasia Institute of Advanced Studies (SIAS)—who hosted and facilitated the entire fieldwork—we engaged with diverse perspectives.

This blog explores key E&D tensions encountered during fieldwork in Nepal, the ethical considerations of engaging in such research, and the ways in which my own background and learning shaped this experience.

1. On arriving

When you arrive at someone’s home, it’s important to learn the rules, practices, and traditions of that household. These are essentials to truly connect or understand. Thanks to the weeks of preparation beforehand, I was able to introduce myself in Nepali, express gratitude, and be respectful. That was my first goal.

Picture 1: SIAS – UoE in Nepal

My second goal was simply to connect. Some homes immediately feel familiar. That’s how I felt upon arriving in Kathmandu. It was comforting to recognize parts of myself on the other side of the world and to connect with others through these similarities.

I feared my role would resemble Parachute Research. That is when researchers from the Global North work in the Global South with no long-term investment, or consideration of ground realities (de Vos, 2022). However, contrary to Parachute Research phenomenon, I felt our presence in Nepal aligned with local priorities thanks to the support of SIAS. Instead of imposing an agenda we trusted the knowledge and guidance of SIAS.

The UoE-SIAS partnership represents one of the solutions de Vos proposes to avoid parachute research: equitable collaborations that value local knowledge and foster long-term investment (de Vos, 2022).

2. Reimagining Conservation: Beyond Coverage and Towards Justice

I believe one of the most impactful statements I heard was during Dr. Bishnu Hari’s presentation, as he shared the historical development of Community Forestry and other forest management regimes in Nepal. Complementing other SIAS presentations from that day, he noted that the linkage between livelihoods and forestry is weakening. He then posed a thought-provoking question:

We can have a bigger percentage of forest coverage, but for what? (Poudyal, 2025)

This question took me back to the early terms of the MSc and the concept of distributional justice, as the analysis of justice from the distribution of burdens and benefits related to environmental interventions (Svarstada & Benjaminsen, 2020). This fundamental dimension of justice invited me to reframe the narrative of conservation to one that reflects the priorities and needs of the people living in these territories.

Nepal’s forest cover today stands at 44%, nearly double what it was in 1992 (Raj, 2024). From a conservation standpoint, this is considered a success. The global narrative suggests that increasing forest coverage is inherently beneficial. Conservation often seeks to keep nature untouched by human intervention, as seen in the mainstream conservation approach (Büscher & Fletcher, 2020).

Dr. Bishnu showed this trend doesn’t match Nepal’s local reality. While national forest coverage has increased, forest use has decreased (Soberón, 2025). This shift in people’s relationship with forests is not only due to livelihood diversification, but also to changes in the social and economic value of land for communities (Poudyal, 2025; Poudel, 2025).

During our focus group in the Chhapeli Community, I was struck by how committed the women were to conservation. Their perspective aligns more with convivial conservation: they see themselves as coexisting with nature, rather than separating from it (Büscher & Fletcher, 2020).

Picture 2: Focus Group in the Chhapeli Community Forest User Group

Photo taken by the author

In light of the lack of distributional justice in Nepal, I agree with Dr. Bishnu’s conclusion: we must reimagine the transformation of the forest-people relationship—not just in Nepal, but globally. Conserving for the sake of conserving may appear to be an obvious tool to address climate change. However, it is a simplistic measure if it disregards the impacts on each community.

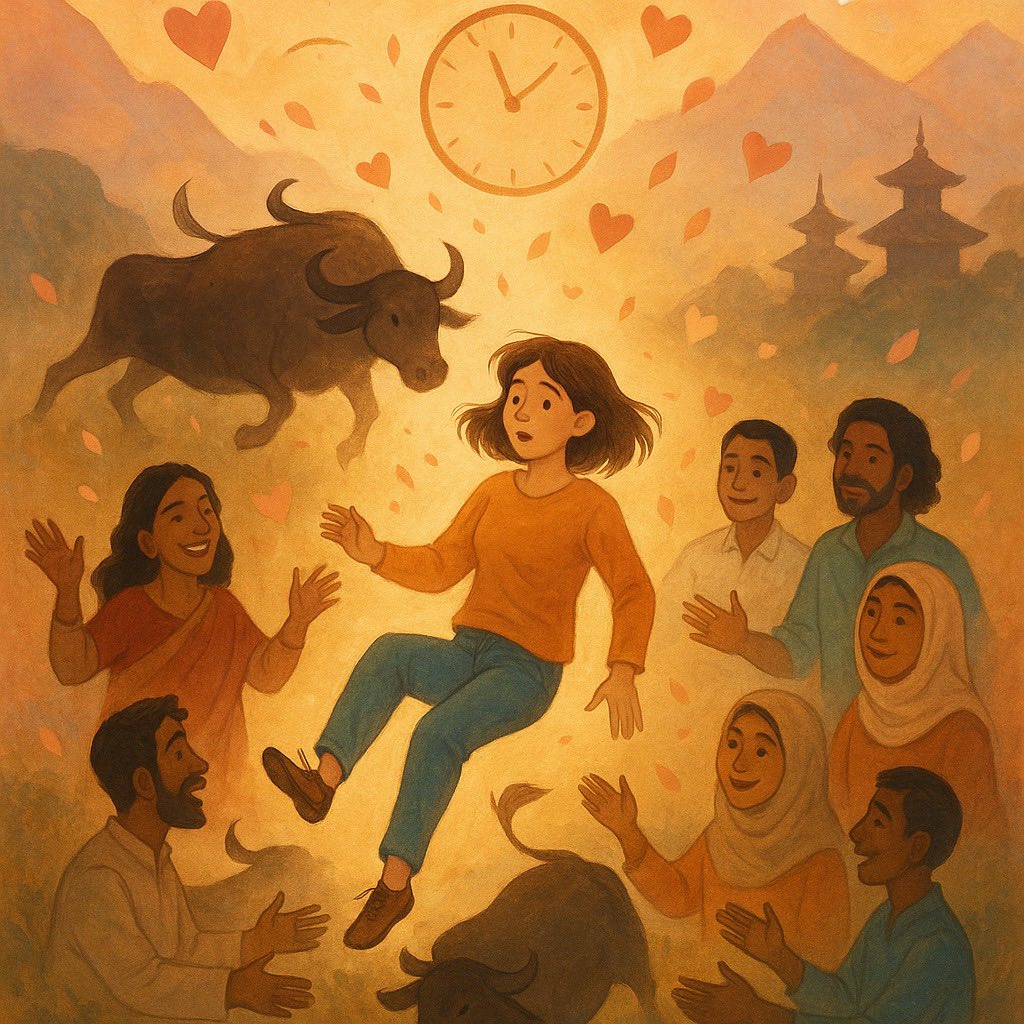

3. On the Buffalo Anecdote

On the last day in Nepal, someone told a story about a friend (A) who had been charged by a buffalo and thrown into the air. Luckily, A had taken a class that taught how to fall properly, which helped her avoid injury.

This trip wasn’t like a buffalo catching us off guard and scaring us with what could happen. Coming to Nepal brought many uncertainties and emotional experiences—some that nourished me, and others that at times overwhelmed me. Time was my real “buffalo”—I often wished I could pause or fast-forward it.

Picture 3: Buffalo anecdote

How did I manage this? Through love. When I was exhausted, I saw others were too—and I didn’t feel alone. We all wanted to live each day fully, which was impossible, but the collective effort gave me strength. That sense of belonging turned the experience into a true milestone.

In this context, “access through love” isn’t just a metaphor. It echoes Guasco (2022): access isn’t a checklist—it’s care, accountability, and collective praxis.

4. Final thoughts

This journey challenged and enriched me by engaging with the ethical dimensions of fieldwork and revealing how my positionality shaped the experience. It deepened my understanding of what just and reciprocal conservation might look like and reinforced the need to approach future work with humility and reflection.

Before the trip, I asked myself: just because I could go to Nepal as a UK-based student, should I? Once there, I realized no photo or article could fully convey its complexity. Being present was essential—especially to learn from partners like SIAS, and from a country that reminded me more of Peru than the UK.

That question of “should I” came up again in Chhapeli, this time in relation to conservation. The key takeaway was clear: each community must define what conservation means to them. No one else can fully grasp their context. We must conserve—but not at the expense of people. Human presence is not a threat to conservation; it is part of it. We are all connected.

5. Bibliography

Büscher, B. and Fletcher, R. (2020) The Conservation Revolution: Radical Ideas for Saving Nature Beyond the Anthropocene. London: Verso.

de Vos, A. (2022) ‘Stowing parachutes, strengthening science’, Conservation Science and Practice, 4(5), e12709. https://doi.org/10.1111/csp2.12709

Guasco, A. (2022) ‘On an ethic of not going there’, The Geographical Journal [online]. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/geoj.12462 [Accessed 28 Apr. 2025].

Poudel, D. (2025) Theme A: Changing Subsistence Farming Practices. Presentation, 12 Apr. 2025.

Poudyal, B.H. (2025) Theme B: Forest People Relations. Presentation, 12 Apr. 2025.

Raj, A. (2024) ‘Nepal PM sums up 2024 shift away from conservation: “Fewer tigers, less forest”’, Mongabay [online]. Available at: https://news.mongabay.com/2024/12/nepal-pm-sums-up-2024-shift-away-from-conservation-fewer-tigers-less-forest/ [Accessed 28 Apr. 2025].

Soberón Garreta, D. (2025) Personal field notes during Nepal trip. Personal field notes, 08–22 April 2025.

Svarstad, H. and Benjaminsen, T.A. (2020) ‘Reading radical environmental justice through a political ecology lens’, Geoforum, 108, pp. 1–11. Available at: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0016718519303161 [Accessed 28 Apr. 2025].

“Views expressed here are personal and not associated with any affiliated organisations”