-Sam Staddon, University of Edinburgh

As I sit here in Tribhuvan International Airport, waiting for my flight back to Edinburgh, I am full of thoughts and feelings about the last two weeks here in Nepal, for our annual SIAS – University of Edinburgh Summer School. Whilst relatively short, the intention of our trip is to allow our Masters students the opportunity to meaningfully engage with the complexity of the Nepali environment and development challenges. We do so by visiting people, projects and places in Kathmandu and beyond, and by practicing group research involving data collection, analysis and presentation. Much of our learning is generated by self and collective reflection – going to Nepal to learn as much about ourselves as about Nepal.

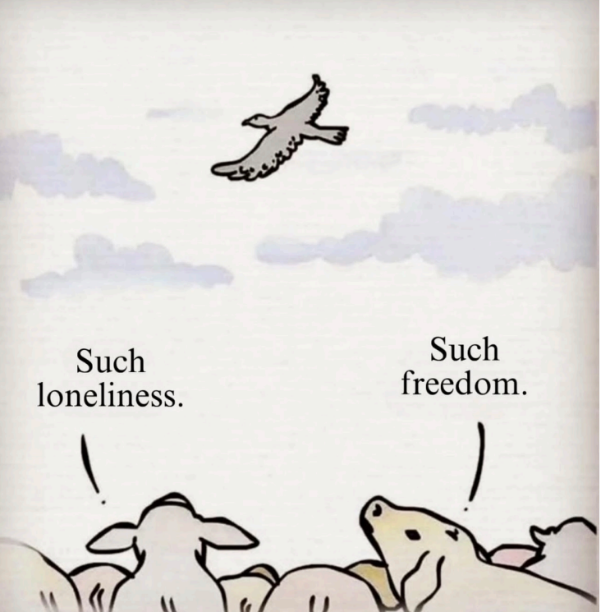

In sitting here reflecting myself, I keep coming back to an image on a slide during a presentation by Dr Govinda Paudel, on behalf of SIAS, talking to us about changing human-wildlife relations in the mid-hills of Nepal. The image (shown below) features a group of sheep staring up into the sky – they spot a bird and two sheep offer their thoughts – one says “Such loneliness” and the other “Such freedom”. Govinda used this image to talk to us about the importance of narratives – and the dominance of some over others – in order to push us to think about how we come to understand and interpret a people, or project, or place. For instance, he suggested that from a distance Nepal’s community forestry programme is a huge success, but he urged us to ask “is it really the same when you talk to the people in those groups?” He also insisted us to be curious, not only about our own assumptions but those of others. On the topic of wildlife, the assumptions and narratives of conservationists and policy-makers have huge consequences for lives and landscapes across Nepal. Whilst these may have positive results for biodiversity, if they do not take into account the lived experiences and emotional labour of those living with wildlife (such as fear and stress, physical attacks and loss of lives, damage to crops and threats to food security), the results can also be deep social injustices. Despite such injustices, during our trip, we heard from people living with wildlife express love for monkeys, with one saying “they destroy, but we enjoy”. This is just one example of the complexity of environment and development challenges facing Nepal, but there are many more, including issues related to water access, disaster risks, farming and food security, and other threats from the climate crisis.

During our trip, we also had the privilege of hearing from Dibya Devi Gurung, renowned for her expertise in gender equality and social inclusion (GESI) in the field of natural resource management. Whilst Nepal is celebrated for its efforts to promote GESI, she too highlighted complexities. She spoke about the need to “dig deeper” in order to try and get beneath the surface of narratives of women’s ‘empowerment’, to ask about those ‘left behind’ as they are not able to participate in forms of community-based natural resource management for various reasons, and to question what more transformational forms of ‘leadership’ might look and feel like. We heard that whilst there are widespread trainings on GESI for those working in environment and development, these are often too short, too shallow and not sustained. Dibya concluded that “investments must match intentions”, meaning that if we are intent on meaningfully engaging with the complexity of social and environmental challenges in Nepal, then these efforts must be appropriately resourced. Resources might include finances, but also skills, expertise, knowledge, methods and approaches that can help in the process and politics of ‘digging deeper’.

These two insights – on the one hand the need to be curious and question assumptions and dominant narratives, and on the other the need to invest well if we are to be able to meaningfully do this ‘digging deeper’ – have got me thinking about our own trip to Nepal. The intention of our trip is to allow our Master’s students the opportunity to meaningfully engage with the complexity of Nepali environment and development challenges, including through learning about themselves. But do our investments match our intentions? And what is the outcome of such investment?

In terms of investments, our students – and their sponsors – make huge financial investments to fund their studies, and it is this resource which ultimately allows our trip to take place. The University of Edinburgh then makes the important choice to dedicate a portion of that funding to the trip, seeing it as a valuable experiential pedagogical endeavour; as a culmination of the year’s classroom-based teaching and learning, and an opportunity for students to put theory into practice, and to embody the kinds of professionals they say in class that they would like to be. As university staff, we attempt to ensure students are ready to make the most of the opportunities the trip offers, not only through prior teaching of theory, but also in a semester of preparation sessions in which they learn something of Nepal’s development history, of its environmental governance, of its language and cultures; and in which they discuss ethics in research, in flying for fieldwork, and in collective and self-care during it. And then months before we even set off from Edinburgh, SIAS staff are working hard ‘behind the scenes’ to plan the trip, to make multiple visits across the country to set up opportunities to visit people and projects and places, to create budgets, to make hotel and bus bookings, to buy our Maiko Chinos ‘Tokens of Love’, and to finish up other work so that staff can be free to join us on the trip.

The common thread in all of these investments is people’s energy, enthusiasm and emotional engagement – both in preparing for and during the trip. We collectively attempt to embody an approach that centres an ethics of care, doing so in order to create a space and time in which we all feel safe to unlearn our assumptions, to constructively question each other, to listen actively, to practice intellectual humility, to feel and engage all of our senses, and to eat and dance and laugh and cry together. Finances are of course necessary, but the ultimate resource for our trips are relationships. In the short-term, relationships with rural villagers and Kathmandu professionals we might only spend a half-day or day with, but who are so warm and welcoming, bringing us not only ideas and inspiration, but also frequently tea and occasionally dancing. In the medium term, relationships with students who give so much throughout the trip each year, going with busy schedules and supporting each other when energies are low. And in the long-term, relationships with SIAS who never stop to amaze us with not only their organisational skills, but most importantly their critical insights and passion, and whom we truly hope to continue working with on this trip for many years to come. In the current climate of financial uncertainty in the UK higher education sector, we dearly hope that the University will continue its side of the investment, to allow this to happen.

In terms of the outcomes of our investments – these resources and relationships – and whether the intentions have been met, I will leave it to our students to judge that – you can read their own reflections on the trips in their blogs for SIAS, which can be found here:

2019

- You and I are no different by Fleur Nash (UoE)

- Beyond informative: When Learning Becomes Transformative by Peter Rowe (UoE)

- On Nepal: Fieldwork Reflections By Sonya Manchanda Peres (UoE)

- Mutual learning experience By Parbati Pandey (Masters student in Nepal)

2020

- Impacts of COVID-19 on Collaborative Fieldwork: A Toolkit for Global Engagement by Allison Wilkerson (UoE)

2024

- The “Fu Ming” People – To the Idealists of SIAS and All Those in Nepal By Yuequi Sun (UoE)

2025

- Nepal and the Path Back to Hope: On Emotion, Self-Reflection, and ‘Development’ By Shabira Damarti, (UoE)

- Because I Can, Should I? Reflections on Conservation, Reciprocity, and Justice from Fieldwork in Nepal By Daniela Soberon Garreta (UoE)

- Critical Hope as a Living Practice: Student Reflections from a Nepal Field Trip By Trace Mdamu (Tanzania), Sharon Wambete (Kenya), Sanjeev Paneru (Nepal), Camil Guo (China), Sitong Shen (China), Panayiotis Louca (Cyprus), Esther Githinji (Kenya)– (UoE)

- GOING THERE: AN EMOTIONAL PERSPECTIVE OF NEPAL FIELD TRIP By Trace Mdamu (UOE)

- To be added in due course!

“Views expressed here are personal and not associated with any affiliated organisations”